The Hungarian Pan

When, in the histories of Cinema and Oppression, has a particular type of shot slipped from the tyrant nation in to the oppressed nation? The immediate answer one may want to give is now, and for the past thirty or so years, and that country would be America. America has had not just one type of shot but an entire array of Hollywood conventions adapted by the rest of the world, for better or for worse (and the implication is usually that it’s for the worst). Yet this is simply a sub-argument of the greater subject of U.S imperialism, and the U.S, for all its’ cultural imperialism, has never done to a country what the Soviet Union did to Hungary. Of course, what the monstrosity of the USSR did to all of Eastern Europe is notable, but here Hungary an exception, first of all, because of the total cultural beating it took; suppression of the Hungarian language, bans of books by beloved native authors who did not fit the socialist cause, official, state approved art, and virtually zero political independence from Moscow, even when other countries were being slightly liberalized. The other reason Hungary is particularly notable is in the way it’s cinema changed in this period. It changed because of one final imposition made by the Soviets, even if it was probably an unconscious one. This was a particular type of shot, more accurately a camera movement, known the Pan.

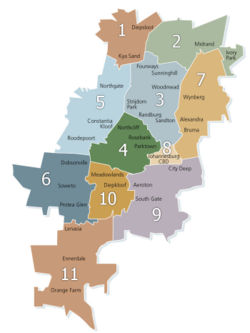

The Hungarian Pan can be exemplified by one or more images from six different films from the period of 1960—the present. These images, and the films which they are from, are:

1. The Round-Up (1965): Black and White. Miklos Janco’s camera moves left to right down the lines of prisoners, in their filthy clothes, their faces dirty, their spirits weakened as they stand in line in front of the Hapsburg soldiers, in the rain. The camera progresses with the militaristic cold of the Austrian soldiers, yet there is a hidden empathy of which the viewer is always aware.

2. Father: Diary of One Week (1966): Black and White. A pan of a young man running across a bridge in stops and starts, rifle in hand, ducking below the concrete banister as gunfire from the Soviet tanks sporadically booms from the city. The street is deserted except for him. Several cuts to closer shots of the man, but always a return to the fitful pan.

3. The Red and The White (1968): Black and White. Sounds of gunfire. A renegade soldier moves backwards aside a rickety wooden fence, firing his rifle at oncoming Russian soldiers. Pan with him along the fence. He dodges into some shrubbery beside a marsh where several other Hungarian soldiers wait. The Russians overtake them and the man runs in to the water. A general or commander asks him to step forward. Pan back in the opposite direction, on to the grass again. The Russian soldier asks the man if he is Hungarian and the man replies that he is. He is told to run back in to the water. He stares at the commander in fear as the commander wades in to the marsh, pulls out a pistol and shoots him dead.

4. Damnation (1988): Black and White. Accordion music. Another line of sorrowful faces, but this time they are peasants, farmers and other assorted townsfolk who gaze in to the camera with a defiant bitterness at their lot in life. The pan starts with rain, but this rain is more like a bucket of dirty water that pours down the gray wall in sheets. Camera moves past one section of peasants and farmers divided by a narrower wall. Then comes another section of peasants and farmers. Following them is another wall, on which another bucket of dirty water falls.

5. Hukkle (2002): Color. A lazy, sunny afternoon in late spring or early summer. An makeshift outdoor bowling alley, put together by idle villagers. One man steps up to the start of the rink and shoots a ball down the alley. It knocks over the wooden pins and the villagers cheer and stand. Pan from left to right with the ball, as the villagers move about and one collects the ball. Stop at the three bowling pins. This shot repeats itself twice, in slight variations.

6. Tranquility (2008): Color. At the start of the film, a door opens in a quiet and dim apartment building in the early morning. Through the warped glass of a windowpane, we pan with a man as he rushes across the hallway. Stop when he walks out the front door, slamming it. Later: Pan with the same man as he runs across the Elizabeth Bridge, linking Pest to Buda, towards the Buda side to go home to his sick mother. The Danube River cuts through the background. He stops for a moment, then turns and starts running in the other direction.

Each pan is slower than the average pan. These pans depict images linked by bridges, poverty or violence. The precision of the individual camera movements have some surprising relationships in rhythm: while several are a simple left-right or right-left dolly, the pans of Miklos Jancso (The Round-Up, The Red and the White) and Bela Tarr (Damnation) are deliberately complex, starting from one direction, moving as far as they can, turning around and moving far in the other direction, transforming in to far more than a pan. Theirs’ are shots that drive at some sort of fulfillment that is always held at bay by hunger and chaos, and each of their films is built from these set-piece style shots. The pans of Gyorgy Palfi (Hukkle) and Robert Alfoldi (Tranquility), on the other hand, are pans that are both strictly functional and consciously in debt to the films that preceded them; though one can only get a sense of this by watching the films. Every pan gives the impression of trying to stave off doom; perhaps this is why several are so fitful. The doom derives from the content: in Hukkle, from the inevitability of another villager dying from a poison that is contaminating their food; in Father, from the fact that the rest of Budapest is in turmoil, and the protagonist could be next. But the doom is symbolic of the country’s struggle during the Soviet era, and in practice it is a clear attempt to not only stave off doom, but also create a national cinematic conscience.

Back in the tyrant country, the U.S.S.R, in which this slow, poetic movement was engineered, filmmakers who used these pans were a mixture of rebels and conformists. Andrei Tarkovsky, son of the renowned poet Arseny Tarkovsky, was a student at the state film school VGIK, where he began honing his long-pan oriented style. From Ivan’s Childhood (1962) onward, and especially in his masterpieces Andrei Rublev (1966) and Solaris (1972), he became the anointed master of the long take, the only comparable director perhaps being Antonioni. Yet Tarkovsky’s long takes were roaming, constant pans, not the stolid social realism that was the norm in the Soviet Union. His films were firmly anti-social realism, and appear to be more influenced by painting—especially icons and triptychs—in their visual styles, as well as poetry. They could not have possibly been made were it not for the liberalization policies of Nikita Kruschev, which allowed for more freedom of expression amongst artists.

At the same time as Tarkovsky, however, there was another film called I am Cuba (1960). This film was a state approved and funded propaganda piece about the Cuban revolution and the beauty of that country’s ideals. Yet the film is only Social Realism in the sense that it promotes Socialism; it rejects the traditional social realist filmmaking of Eisenstein and Vertov in favor of the same long, roaming pans of Tarkovsky. At the film’s opening, the camera tracks along with a man standing in his fishing boat, coasting along a shallow river with the occasional stroke of his paddle. Later, it tracks through a nightclub and still later, down the steps of the Cuban Parliament, in what may be a somewhat ironic homage to Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin (1925). The film is gorgeous to look at, yet it is still a piece of propaganda; a surprising piece of propaganda at that. The very fact of its stylization is evidence that even this film could not have been made without the same effects of the liberalization period under Kruschev. This is the very same reason Hungarian filmmaker’s were able to develop their own brand of the pan; Khrushchev was slowly, cautiously, allowing them to aid their cinema.

Still, did Hungarian filmmakers really ‘take’ their pans from the Soviets, or did the two countries simply develop the same aesthetic at the same time, by coincidence? It’s a fair question to ask, and there is some evidence of Hungarian filmmakers showing a flair for the pan as early as 1956, in the national classic The Merry Go-Round. The pans in that film—of a happy girl on the spinning Merry Go-Round of the title—do not bear much technical or thematic resemblance to the pans that came later, though. The question becomes irrelevant when we consider how the Hungarian Pan is and was always more meaningful than the Soviet Pan—or any other filmmaker’s pan. In the Soviet Union in the 1960’s and 70’s, films were either propaganda (I am Cuba) or anti-propaganda (Tarkovsky’s films). In Hungary, movies were about the vagaries of existence, about survival and yearning for freedom, and many still are. The Hungarian Pan reflected this theme; in fighting the Russians and the Austrians; in the hesitation of whether or not to return to one’s ill mother; in the dirty faces of peasants and the work they do.

.

Yet the two filmmakers mentioned here who have truly utilized the Hungarian pan to it’s fullest potential are first Miklos Jancso and then Bela Tarr. Both have made the long, roaming pan one of their trademarks in film after film and Tarr has freely admitted to Jancso’s influence. Does the pan then belong merely to these two filmmakers and not the whole of Hungarian cinema? A fair answer is no; Jancso has made most of his films about a part of Hungarian history, and so his cinema—and therefore it’s means of expression—is intentionally, unabashedly nationalistic (that The Red and the White was a co-production with Russia is also symbolic). Tarr’s best known films are expressive of life in Hungary’s Alfold, or, Great Plain. While not nationalistic, he is representative of his country’s cinema these days, and more recent filmmakers such as Kornel Mundruzco (Delta) have strongly taken after him. Tarr and Jancso are the towering individuals of Hungarian cinema; the pan, by the very nature of their films, remains national.

In Russia, filmmakers such as Alexandr Sokurov and Andrei Zvyagintsev have continued the tradition of the Russian pan, in obvious debt to Tarkovsky. In their films, there is not a single Hungarian. Their films follow the painterly framework created by Tarkovsky. In Hungarian Pans, though, what is most striking is not the simple aesthetic beauty of the shots, but oppression, which is implicit if not overt. Russians feature in their pans not infrequently, and the most menacing pan of them all may be from the footage shot in 1956, by an amateur or news cameraman, of Soviet tanks rolling through Budapest. The grainy Black and White footage veers from left to right as a tank dotted with white stars rumbles through the rubble of Budapest, part of a long line of tanks. This image, like the other quintessential Hungarian Pans is un-painterly, and speaks of a form of oppression. This oppression was very real for the Hungarians for many decades, and perhaps the best Hungarian filmmakers can still feel it. It has created a shot that is the one thing for which we have to thank the brutal and extinct regime known as the Soviet Union.

Thanks to:

The Hungarian Cinema: from coffee house to multiplex, Chapters 6 and 7; Cunningham, John; Wallflower Press, 2004.

For assistance in with writing this essay.

Films Noted and pictured are:

--Szegenlegenyek (The Round Up): Dir: Jancso, Miklos. Scr: Hernadi, Gyula. MAFILM IV, Jatekfilmstudio, Hungary, 1965.

--Apa: Egy Hit Naploja (Father: Diary of a Week): Dir: Szabo, Istvan. Scr: Szabo, Istvan. MAFILM IV, Jatekfilmstudio, Hungary, 1966.

-- Csillagosok, Katonak (The Red and The White): Dir: Jancso, Miklos. Scr: Hernadi Gyula, Jancso, Miklos. MAFILM/MOSFILM, Hungary/Russia, 1968.

-- Karhozat (Damnation): Dir: Tarr, Bela. Scr: Krasznahorkai, Laszlo, Tarr, Bela. Hungarian Film Institute/Mokep. Hungary, 1987.

-- Hukkle: Dir: Palfi, Gyorgy. Scr: Palfi, Gyorgy. Mokep. Hungary, 2002.

-- Nyugalom (Tranquility): Dir: Alfoldi, Robert. Scr: Alfoldi, Robert, Gyaraczi, Laszlo, Berenyi, Betti (from the novel by Atilla Bartis). Magyar Televizio/Unio Film. Hungary, 2008.

-- I am Cuba (Soy Cuba/Ya Cuba): Dir: Kalatozov, Mikael. Scr:Barnet, Enrique Pineta, Yevtushenko, Yevgenyi. Goskino/ICAIC. Russia/Cuba, 1964.

(

( (

( (

( (

(