District 9 is a film spilling over with anarchy and nihilism, though maybe the filmmaker’s didn’t know it.

The director is Neil Blomkamp, a first-time feature director and native of South Africa who made the film with the ‘small budget’ of $30 million, much of it on loan from producer Peter Jackson. Jackson let the director cut loose, and there are as many explosions, gun-battles and shaking cameras as one could squeeze in to such a film, though all are framed by an uncommonly clever story. A massive alien spaceship has been hovering over Johannesburg for over twenty years, while it’s crew, comprised of thousands of insect-like, tentacled aliens have occupied the ghettos of the city. By 2010, the government and residents of the city have become fed up with the aliens and a team is created to deport them from their current occupation in to a designated site called District 9. The team is led by Wikus (Sharlto Copley), an irritating, arrogantly jovial man who may have been hired for the job simply because he is married to the daughter (Tania Haywood) of a top government figure. Naturally, the aliens are uncooperative and Wikus is not the right man for the job; but once he accidentally swallows a brown alien substance found while raiding one of their shacks, he slowly begins to transform in to one of the aliens (known as ‘Prawns’) himself, and becomes a target of the government. While on the lam, he is forced to rely on the alien in whose shack he found the substance, and who claims he can turn Wikus back to normal.

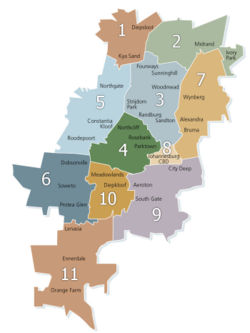

(Map of District 10, Johannesburg, South Africa)

One of the most memorable snippets of the film is one that occurs by-way of Blomkamps storytelling form of choice; a mixture of straight documentary, sequestering the action-packed plight of the rest of the story. The snippet is in a documentary segment near the beginning, in which a T.V commentator is talking about the plan to take care of the aliens, and mentions the opposition of human rights groups. There is a quick shot of activists holding signs and shouting in the streets, and in the context of this story it seems completely zany, but it is meant to be taken at face value. Because District 9 is almost a merely inspired, bombastic science fiction film that adheres to the pulpiest aspects of the genre, except for one thing; it’s an allegory of Apartheid. Blomkamp deserves credit for choosing such an ignored subject of cinema and framing it in such a peculiar way, but the internal flaw of the allegory is that those were Humans and these are Aliens. By way of it’s documentary realism, the film is asking us to remove ourselves from entertainment and seriously consider: What if Aliens landed here on Earth? It’s own answer to the question only begins with the shot of human rights activists, and although hilariously accurate, Blomkamp doesn’t want us to think it’s hilarious; it is just dead accurate. These people on the margins, these protestors, have the right idea about how to live with these creatures, while the majority of South Africans are prejudiced and the totalitarian government simply has it’s own agenda. But when I considered what would happen if aliens really landed on earth, I quickly realized that I would fully support a plan to get them out of here as quickly as possible. The aliens in this film are mostly portrayed as brutish and not very intelligent, have been hanging around for over twenty years, and posses weapons; some of them kill. With all this considered, a program to put them far away from human civilization looks reasonable enough. That one alien (and his cute son) do gain our sympathy in the film, as we spend more time with them, does not save the overall allegory. Blacks are people and are entitled to human liberties; aliens are intruders, and their predicament makes human rights activists look silly.

Yet what ensues is far more, even, than a socially conscious sci-fi action film. District 9 contains, as one other critic put it, ‘bravura storytelling.’ This is ultimately the emotional sum of its parts. On one hand, it’s story is indebted to the stories of trade paperback science fiction magazines of old that have now been consigned to used bookstores and special collections. Yet those stories did not utilize grainy surveillance footage, CGI-created characters, or T.V imagery; in these respects, the story is indebted to modern technologies. Also thrown in to the mix are the slow-motion shots that occur in films when a character is getting ready to take care of business, and a token baddie, ordered to capture Wikus, who comes in to the film late and acts as if he’s at a frat party the entire time. Given this intense mixture, Blomkamps storytelling approach involves both caricatures and fleshed-out characters, genre clichés and inspired visual sensibility.

All bravaura storytelling encompasses both talent and fault, and there are several major talents at work here; one is the lead actor Sharlton Copley, who manages to hold every scene he’s in back from all the CGI and gun-battles and misguided satire. He is a true performer who does not need to be an action hero to make us keep our eyes on him, even in spite of his ridiculousness. And the cinematography, by newcomer Trent Opaloch, can be a real visceral wrench; watch as he cuts back and forth between Tania being assured by her father that her husband is dying and she has to ‘let go,’ and shots of Wikus being wheeled, screaming, in to a spooky government operating room where his surgeons intend to cut his heart out. But bravura storytelling needs to be anchored in fundamental storytelling, and District 9 fails to follow through on several of its fundamentals. All allegories must be logically reconciled with that which they represent in reality; all clichés and caricatures will not necessarily be mitigated by the audaciousness of other aspects; and all those protestors may be where the actual satire resides.