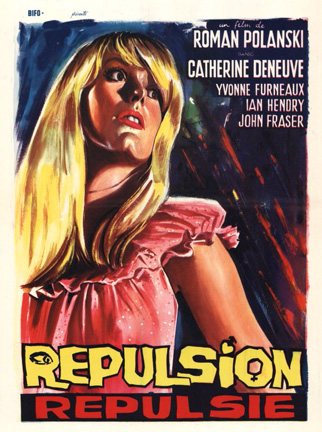

The first two shots of Repulsion are exemplary acts of cinematic object-worship. They show Catherine Deneuve’s eyes, almost unblinking, as the credits scroll over her pupils. The character Denevue plays is Carol, and she is a woman who will be abused relentlessly throughout the film—by men, both real and imaginary, by her petty sister, by herself, and by Polanski’s camera.

The story is simple enough to give the impression that the film is one elaborate film-school-ish exercise, or just a step-by-step manual on how to make a psychological thriller. Carol and her sister, Helen, live in a flat together in London and work at a Beauty salon. Helen has a boyfriend with whom she loudly copulates each night as Carol tries to sleep. Carol is a severely withdrawn, yet beautiful girl. A man asks her on a date and she accepts as if accepting something in a dream. She spends more and more time in her apartment, becoming obsessed with cracks that she notices all over the walls, with the constantly ringing phone and with the bizarre food she accumulates (though we never see her eating it). When her sister goes on vacation with her boyfriend, Carol’s madness intensifies. The cracks get bigger. The walls turn to clay. A stranger appears in her room and rapes her each night. Eventually, she will commit murder.

Much of this is an excuse for good old pure cinema, of the shock-value sort, and it’s a good enough excuse. The rape scenes are silent except for a ticking clock (leaving the 60 Minutes theme open to very sinister interpretations). Polanski is obsessed with tracking shots of Deneuve, for no particular reason other than that they look impressive. The score uses jazz music extensively, sometimes with the tracking shots, sometimes with more surprising associations, like a murder scene. One shot lasts for some time past it’s legal expiration, in order to focus on several street musicians as they cross the street playing their instruments. There is no reason to believe that the filmmaker’s did not get a kick out of the sleek, unhinged mood of the film, and their cinema for the sake of cinema gives us a kick out of it, too. Yet the film, with it's skittering jazz score, fashion styles, and implication of the sexually liberated young person (not the protagonist), gives a whiff of the coming 60’s counterculture. It was made at the very start of the ‘swinging 60’s’ period, and this is part of the overall milleu.

What is more controversial is the way in which Repulsion indulges in objectification and idealization of female sexuality. This is one of the most sexist films ever made, though not quite mysoginistic. Carol is an infuriatingly blank and vulnerable woman, yet she does have the guts to kill a man, and may have suffered abuse in her past. One of the men in this film is a genuine pervert; another is a well-intentioned guy whom Carol perceives as a pervert. Carol is simply horrified by men, and her levels of sexual repression are vast enough to be unbelievable—just look at how gorgeous Deneuve is—and ambiguous. Perhaps Carol is a lesbian, whose attraction to women only comes through in a scene when she is loosening up and laughing with, and almost touching, a female co-worker, before looking away in shame. Or perhaps she is terrified by mere physical contact, and the physical attributes particular to women; the potatoes that lie on her kitchen table come to resemble ugly, dead things, similar to fetuses. A family photograph hints at possible familial abuse from years before. The way in which the filmmakers handle this ambiguity is by relentless objectification of Deneuve; close-ups of her face and eyes as she is raped or grabbed by hands that come out of the walls; her increasingly skimpy clothing. Yet Deneuve asks for this sort of treatment by way of her freakish, trembling performance. How are we not supposed to project our interpretations of the source of this woman’ sexual repressions when she is so thoroughly uncommunicative and unceasingly mad? One thing Polanski fortunately does not do is turn the story in to a righteous pulpit so popular with stories of madness in the cinema: it’s not Carol who’s crazy, it’s the rest of the world that doesn’t understand her. No, this woman is simply, frighteningly unnatural. Repulsion falls firmly in to line with all the other films that objectify women and their sexual mysteries, going all the way back to D.W Griffith’s An Unseen Enemy and continuing with Ecstasy, Belle Du Jour, Deep Throat, and even Mulholland Drive. Repulsion may be the most unsettlingly proud film of it’s kind; it looks at a sex-object, builds her character through further sex-objectification and invites the audience to rejoice in it. (An Unseen Enemy, 1912)

(An Unseen Enemy, 1912)

(Deep Throat, 1972)

(Deep Throat, 1972) (Ecstasy, 1933)

(Ecstasy, 1933)

(Mulholland Drive, 2001)

(Mulholland Drive, 2001)