Why should we take Psycho seriously fifty years on? One would expect that by now, the film would have been usurped by one the many films that have followed. Perhaps consensus would now claim The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) as the great horror masterpiece. Maybe The Sixth Sense (1999) would have by now become the chiller to end all chillers. Even a remake had the potential to steal the original’s fire; Gus Van Sant did exactly that in 1999, only changing the look of the film from Black and White to Color. But it had utterly none of the same impact, even for people who had never seen the original. The failure of the remake seemed to prove that there wasn’t anything inherently thrilling about Psycho’s imagery and that its story was no longer something special. But if all of the films that were markedly influenced by Psycho have been written off as either pure popcorn junk, or an entertaining-thriller-that’s-only-a-movie, why is Psycho more than just an entertaining and clever thriller? Why is it more than only a movie?

The clearest answer is its director, Alfred Hitchcock. This year also marks the 30th anniversary of his death. And lest this essay turn in to a mere call for retrospectives (right now, it is), let’s examine why it is that this portly, self-effacing Brit could create what is probably the most lasting achievement in popular cinema. Let’s see what it says about the legacy of horror films today.

(The making of Psycho will only be vaguely mentioned here. For a good summary of its development, read Francois Truffaut’s interviews with Hitchcock, Hitchcock/Truffaut. More recently, David Thomson has written an excellent book called The Moment of Psycho that also gives a good amount of behind the scenes information. There are numerous other sources where one can find information on the production. However, I consider it largely irrelevant to this analysis.)

Hitchcock had most of his career behind him by the time he made Psycho. Most critics in America at the time agreed that his glory days were past. He had produced taut, exciting British mysteries in the 1930’s such as The Man who Knew Too Much (1934) and The Thirty Nine Steps (1935). But ever since he’d come to Hollywood, he had become a sellout, churning out film after film with a roster of glamorous stars and predictable formulas. Andrew Sarris, in his enthusiastic review of Psycho in The Village Voice, crystallized the wrong-headedness of this attitude1. Hitchcock had, in fact, turned out the masterpieces Rear Window (1954), Vertigo (1958) and North by Northwest (1959) amongst other debatable masterpieces. But Psycho, wrote Sarris, was “…the first American picture since Touch of Evil that could stand with the great European films.” “Hitchcock,” Sarris wrote, “is the most daring avant-garde filmmaker in America today.2”

Sarris’ review may be hyperbole, but he was on to something when he called Hitchcock an Avant-Garde filmmaker; the implication being that Psycho is an Avant-Garde film. Psycho is certainly one of the stranger masterpieces any filmmaker has crafted late in their career. Hitchcock was sixty when he made it. His career had been drenched in Technicolor for years and his heyday should have been behind him. Actually, it was. So Hitchcock took the crew from his television show and shot the film in Black and White. He was not returning to his earlier days of filmmaking with this approach; the Black and White in Psycho is not polished as it was in his early films, but grainy and un-ravishing. The images it cloaks are unsettling representations. Sharp objects threaten us when we least expect them to; piercing rain on a car windshield, the beaks of stuffed birds, a knife. Soulless black holes turn up at several significant moments; first, the sunglasses of a policeman who becomes suspicious of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) the anti-heroin who meets her grim fate, then the drainpipe in the shower Marion is murdered in, then the swamp that her car sinks in to after her murder is covered up. Some scenes depict everyday realities nobody talked about; the first scene suggests the aftermath of sex, a toilet bowl briefly becomes a central character. Sometimes the camera creeps in to doorways, sometimes out of doorways. All landscapes are equipped with shadows. The film is built on shadows of the Avant-Garde.

What Hitchcock was doing was taking the scratchiness of B-movies and melding it with the pre-apocalyptic cynicism of film noir. This style gave us imagery that implied things people only thought about in their most anti-social moments. It was imagery that threatened us with its un-cleanliness when it didn’t threaten us violently. All the imagery and story in Psycho came together to make a rare thing in a mainstream film; an appeal to the undesirable. It was an irrational approach. Similarly, the entire film would follow a pattern of irrationality and representational imagery. Because of this pattern, Psycho can roughly be categorized as Avant Garde.

All this might make far too obtuse a film if the story didn’t begin with such bitter simplicity. Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is a secretary with a boyfriend, Tony (John Gavin), whom she meets with for sex in hotel rooms. Both she and Tony are strapped for cash and want to get out of Phoenix together, but cannot. Marion goes back to her dull secretarial job and happens to come across $40,000 dollars she is supposed to transfer to the business account. Instead, she takes the money for herself, driving away from work to who-knows-where. Unfortunately, she is spotted by her boss as he crosses the street, wondering why she is leaving work early. But Marion takes off anyway.

This is the first sign of irrationality in the film; why does she spontaneously steal so much money? Why doesn’t she let Tony know? Marion is like a femme fatale working towards he own destruction, not caring about where she ends up, just that she has a lot of cash and that she isn’t in Phoenix.

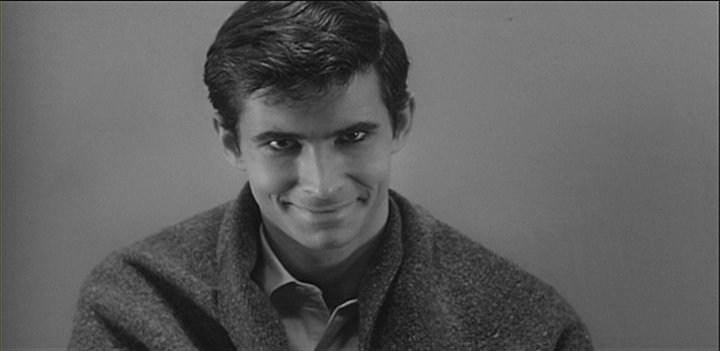

She sleeps in her car overnight, attracting the attention of a cop with soulless, black sunglasses. When he questions her, she is nervous and evasive. She keeps driving and he follows her. Marion trades in her car for another one at a retailer outlet somewhere along the way, but this decision is far more foolhardy than clever. The cop is still on to her and her theft will be discovered in only a matter of time. She drives in to the night, through the stabbing rain, and decides to stop at an out of the way motel called the Bates Motel. Here she meets the neurotic, if sweet-seeming Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), who has been managing his motel alone for some time. She is the first visitor in a while. He puts her in cabin 1 and is clearly taken with her; they have a simple dinner consisting of sandwiches.

It is around this time when the story introduces its next major irrationality; Norman clearly has something wrong with him and he’s clearly becoming the center of our attention. Why does Marion decided to stay here? Why are we so charmed by this creepy new protagonist? He stuffs dead birds as a hobby (they decorate his main cabin). He has a mother who lives up the hill, apparently indisposed. We hear her scold him for having a girl stay in the motel (how does she know?). He both hates her and is co-dependent on her. When Marion suggests that he should “put her away,” Norman leans forward and becomes angry (“You mean a mad house?”) His flare-up suggests that he may have once been in a mad house himself. Marion apologizes for sounding rude and goes to her cabin. In one of the most representational, irrational and all-around memorable images in popular cinema, Norman spies on Marion through a peephole in the wall, his lifeless birds rising above his head, aided by intense shadows.

What is Norman planning? We sense at this point that Marion is in trouble. She counts out the money she stole, deducts a small amount and flushes the rest down the toilet in the glaring white bathroom that will host the film’s most unavoidable scene. Norman goes back to see his mother, looking torn and bitter. Marion undresses and gets in the shower.

Then comes the scene that is impossible to ignore; when Marion Crane is killed in the shower. The forty-five short takes consisting of a knife plummeting and rising, a girl’s bare skin, the shadowed outline of a female figure doing the stabbing, all sprayed by the shower water, shocked audiences in 1960. If there hadn’t been such a big deal made about it, we would be just as shocked today. As it stands, the shower scene nowadays is an obligatory thrill; we know it’s coming, we know what the outcome is and we probably know who did it, but if we’re not thrilled by one of the most astounding rug-pulls in all cinema, then we must be brain-dead. Yet what we don’t immediately grasp about the scene, even today, is how unreal it is; Bernard Hermann’s shrieking strings, Marion’s jaunty screams, the blood that doesn’t even look like blood as it swirls down the plughole. Marion’s wide eyes on her face lying dead on the bathroom floor, as her body lies slumped over the bathtub, as if she is some sick model doing a pose. None of this is how a murder scene should look, to say nothing of the likelihood of such a murder happening at all. The scene is too arranged, too fast, too black and white (in both senses). But this is the ultimate irrational appeal in Psycho. In its completely outlandish composition—while technically a skillful use of Eisensteinian montage-- this scene is the summary of all Avant-Garde tendencies within the film. When we consider its unreal-ness, the thrill we feel is genuine.

This is the first half of Psycho and indeed the best half. Many critics, even admirers, have taken jabs at the second half of the film. After Marion Crane is murdered and Norman cleans up after his mother’s crime, the film becomes too calculated, no longer motivated by character, and too expository2. It leaves us waiting for an inevitable conclusion—Norman’s capture and the discovery of Marion’s body—without any zingers thrown in. It has a final scene that attempts to explain Norman in clinical terms and thus dulls his mystery. But if we’ve been in our seats for the first fifty minutes then we probably won’t leave them. Also, cinema is a fragmented medium where a few good bits can compensate for all the rotten ones.

Psycho’s second half offers a few very good bits, but the reason I think it works is because it cleverly aims towards a naturally desired explanation—what made Norman Bates the way he is—while following characters who won’t ever comprehend it. When the film picks up with Sam and Lila (Vera Miles), Marion’s sister, the literal shadows disappear. Instead, we get to know two human shadows. These people act mechanically, without much emotion and don’t seem to care that a loved one is missing so much as that something has disrupted the way every day life is meant to pass. Money is missing and girl isn’t there; how to restore these things to society?

So they journey through the daylight, anxiously soliciting a few people for help; a detective named Arbogast (Martin Balsam), a sheriff (John McIntire) and eventually Norman himself. Arbogast is killed off in a shocking scene that David Thomson has rightly called “Hitchcock at his best and worst3.” The appearance of Mother from her bedroom, seen in an overhead shot, is frightening, but the way that Arbogast falls down the stairs as she stabs him looks hokey, and we feel as though a detective like him should be prepared for such an attack4. But we cannot forget a scene shortly following, in which Norman gives an ultimatum to his mother to stop killing people or he’ll lock her down in the cellar (another soulless black hole). The camera does not show the conversation, instead tracking away from the doorway to Mother’s bedroom, only spotting Norman as he carries her out down the stairs. Even Hitchcock’s camera does not want to be a part of the explanation; the only difference between it and Marion’s survivors is that it has a good idea of the sheer ugliness of the truth.

When we pick back up with Lila and Sam, we have no choice but to take their side. There is a palpable chill we feel the first time the matter-of-fact sheriff says; “Norman Bate’s mother has been dead and buried in the Green Lawn Cemetery for the last ten years.” And who will forget the masterfully oriented climatic scene in which Sam struggles with Norman in the motel lobby while Lila ventures through the house and peeks in at artifact after artifact of Norman’s psyche? Who can forget the perfectly timed shock of Lila’s enquiring “Mrs. Bates…” as the woman sitting in the chair in the cellar is turned around and revealed as a skeleton?

These good bits frame two programmed, emotionally cold people getting in way over their heads. First we took the side of Marion, a bad girl, then we took the sides of her sister and boyfriend, society’s robots, even though we didn’t want to admit that our sympathies kind of lay with Norman for most of the time. That image of a skull being imposed on Norman’s as he sits in a mental ward face at the very end may be a gimmick, but it is an earned gimmick. Norman found us.

I do not mean to suggest that Psycho is a social commentary, contrasting a mad man with “normal, decent people”. It is primarily a well-crafted story. Hitchcock needed movements in his films; the first half of Psycho is a black, noir-ish crawl, punctuated by Norman Bates. It culminates in a wild montage that comes out of nowhere but fits perfectly. The second half is a practical backtracking, this time viewed from a no-fuss perspective. It leads to the inevitable (alright, disappointing) conclusion. What is constant in both halves is a preference for close-ups and medium shots, with wide shots only there to tease us with what we can’t see; the hotel at the beginning and the house Norman’s mother lives in are the two most obvious examples. The first half establishes the orientation of a large house way out in the desert, uphill from a motel; the second half toys with that orientation. All these elements are combined with the grimy photography of Robert Burkes, the bout of pure cinema that is the shower scene and yes, the suggestion of social comment. It is not Hitchcock’s finest film because it falls too heavily under the weight of its whodunit expectations. But it is one of the boldest stabs at melding traditional genres with stylistic weirdness and combining sound film conventions with tried and true visual intoxication.

It is this blend of moving image craft and deep morbidity that makes Psycho so perverted and unsettling; it is only because what is at first a fear of the unknown is confirmed as something so grotesque that Psycho can be said to "horrify" us. This makes Psycho the ultimate horror film. Yet perversion and morbidity became the only goal of the horror film from there on out, to the overall detriment of cinema. Hitchcock’s irrationality became mainstream cinema’s ridiculousness. He could not have wanted only the most sensationalistic tropes to become the point, because Psycho plays a vital game with the audience that later horror films miss entirely. Hitchcock wanted this game to be expressed in something like that great image of Anthony Perkins peering at Janet Leigh through a peephole in the wall, his neck and lower body shrouded in darkness; rigid, stuffed birds rising up in the background, before cutting to an image of Leigh undressing. When Psycho was released in August of 1960, this scene communicated the entire film to audiences. It said: Peekaboo. Didn’t think this was a trap? Well, it is.

1: Sarris, Andrew, review of Psycho; appeared in The Village Voice, August 11th, 1960

2,3,4: Thomson, David, The Moment of Psycho: How Alfred Hitchcock taught America to love murder. Basic Books, 2009.